While Ha Bik-chuen lived, his wife and children rarely ventured to the rooftop space just above their home in an eight-storey tong lau in To Kwa Wan. He had appropriated it for his library and studio, and they dared not disturb him while he worked.

A self-taught artist whose career began in the early ’60s, Ha delved into a range of visual arts, from painting (Chinese and Western) to printmaking, photography and sculpture, especially using found objects.

When he died at the age of 84 in 2009, Ha left behind an enormous cache of photographs, collages, clippings of articles on exhibitions and other items that are only now being sorted, presenting a side of the artist that few knew about and offering a glimpse into his creative process.

A fraction of this is on display at the Asia Art Archive (AAA) premises on Hollywood Road. Titled «Excessive Enthusiasm: Ha Bik Chuen and the Archive as Practice», the exhibition is aptly named because his studio was crammed with overflowing bookshelves, boxes of cut-out scraps, stacked files, scrolls and paintings that were meticulously filed in his idiosyncratic way.

«It’s exciting,» says researcher Michelle Wong Wun-ting, who heads a team of archivists at the AAA, which has spent the past two years going through the collection donated by the Ha family. «This archive is something the Hong Kong art ecology has known about for a long time, but they haven’t actually seen it.»

It will take the team a few more years to catalogue everything, but the immediate priority is to find a safe place where they can store the bulk of Ha’s hoard. Part of the ceiling in his studio has collapsed and the leaks have led to encroaching mould. So while some items have been moved to Spring Workshop in Wong Chuk Hang, they must quickly find a new home for the rest of material before it deteriorates further.

The artist’s son, Alexander Ha Cheuk-hung, believes the AAA will do his father’s legacy full justice; he had visited their premises two years ago and was moved to tears by how carefully they were preserving his father’s materials.

«He told me and my mum that when he died, he wanted to bequeath his artwork and items to Hong Kong, not to one person but to the city,» he says.

Supported by a multiproject grant from the Arts Development Council, Wong and her team first began their task by examining Ha’s exhibition material.

He was an enthusiastic photographer and from the 1960s to 2000s, documented more than 1,500 exhibitions of local and overseas artists, taking pictures of people who attended as well as the exhibits. Over 40 years that added up to a huge haul: the team has already identified 3,500 contact sheets produced over 17 years and estimates Ha took more than 100,000 photos of exhibitions.

His visual records challenge the notion that art history is virtually non-existent in Hong Kong, Wong says. «There is a desire for a single epic narrative of art history. This is how Western art history has been written and how we’ve been educated. But this doesn’t work in many places in Asia, including Hong Kong. [What we have] is a pregnant ground of different ways of interpreting art history.»

Gallery owner Johnson Chang Tsong-zung of Hanart TZ, who has staged several exhibitions of Ha’s works, recalls the artist was usually busy snapping away on each occasion.

«It never occurred to me to take pictures of the show, but Ha did, and even sent us a few copies afterwards,» Chang says. «He was documenting these exhibitions through his eyes. I wouldn’t say he was a documentary photographer because they are his own experience of the exhibitions, but their documentary aspect is invaluable in recording Hong Kong’s art history.»

Besides taking photos, Ha also collected exhibition catalogues and cut out newspaper and magazine articles about them, building his own archive of the local art scene.

Some speculate that this was his way of educating himself about art, Wong says. «He didn’t go to art school, but it doesn’t mean he didn’t learn. He went to these shows to learn.»

But their biggest find has been a set of labelled boxes containing magazine images that Ha had either kept as visual stimulus or for later use in his works.

Alexander Ha recalls: «When I was young, in the afternoons we would go to Central where Wing On [department store] used to be, and scour office buildings where they dumped piles of magazines. He would pick out titles like National Geographic, Time and Life and I’d help him carry them back.»

His father would browse through them all and, during spare moments, would cut out articles or pictures and file them away in used yellow Kodak film boxes. «When something happened in the news or certain topics cropped up, he would get the pictures out and paste them in books.»

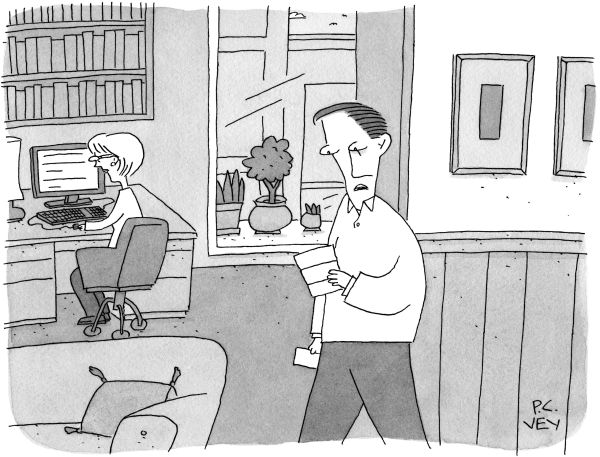

They discovered Ha was using interior design books as a sort of matrix, where he would painstakingly glue photos, pictures of paintings or magazine images and articles so they appeared part of the decor or publication. There were more than 20 books treated this way.

«We had to go through the books, page by page, and feel them by hand to see if he had glued something on it,» Wong says.

Alexander Ha believes these collages were part of his father’s creative process, where he would work through ideas that were later made into prints and sculptures. «They might even be works of art themselves. There’s definitely some kind of humour, a visual play, especially the ones with Chinese headlines.»

On display to the public for the first time at the Asia Art Archive, the books of collages reveal a side of Ha that no one really knew — even gallerist Chang and friend and fellow artist Gaylord Chan Yu-sang were not aware of this practice.

Although Ha’s wife, Leung Siu-mee, assisted with his work, she was not sure how he put it all together; he died without leaving a journal or guide to the filing system, his collection of reference books, photographs and boxes of cut-outs.

As a result, Wong says there is a lot of room for interpretation, which makes going through his cache akin to navigating a maze or trying to chart a map.

Chan, another self-taught artist who was Ha’s contemporary, says his friend started making prints when he became fed up with people copying his relatively successful Chinese-style handicrafts.

«He saw how some artists were making money selling prints and wanted to do the same,» Chan recalls. «He bought a book on printmaking to learn how to do it.»

Later, Ha began creating sculptures from found objects, «mostly because [the material] was free».

Ha belonged to a group of artists who made art even though there was no market and no recognition, Chang says.

«They did this even though they had no institutional endorsement, unlike mainland artists who are backed by institutions like China Academy of Art. He was doing art because he had a passion for it.»

For Michelle Wong, there is a personal connection to the project: her father Ronnie Wong Lai-keung, a trained illustrator and high school teacher, was friends with Ha and they often visited his flat when she was a child.

«When we were going through the photographs of exhibitions, we found more than one album of my dad’s work in there, and I even found a work of my dad’s that he gifted to Ha.»

What was initially intended to be a two-year project will likely take many more years, and the AAA will need to secure more funding to complete the cataloguing.

«We all keep stuff, we all keep personal collective memories. The visuality of things speak to us,» Wong says.

Alexander Ha is glad his father’s legacy is in good hands. «When Chinese people pass away, their family burns things for them. Asia Art Archive is digitising his things so I like to think he’s seeing them in heaven.»

Source: